Buy your UFFIZI GALLERY TICKETS now and avoid LONG QUEUES!

Filippo Brunelleschi’s biography, life, and works

Filippo Brunelleschi was born in Florence in 1377 and started working as a goldsmith, skilled in metalworking and wood sculpture (such as the crucifix in Santa Maria Novella in Florence). After several trips to Rome, including one with Donatello in 1402, Brunelleschi shifted his focus to architecture while still maintaining occasional interest in painting and sculpture. He was also a scholar of applied mathematics, blending his intense humanistic education with a scientific perspective to conceive and construct spaces rationally measured.

In 1409, the artist began working on the Santa Maria del Fiore church construction site in Florence. By 1418, he started interventions for the dome’s construction, which he designed with new technical and aesthetic criteria.

In 1445, Florence’s Hospital of the Innocents (Spedale degli Innocenti) was inaugurated, although it still needed to be completed. This was the first building entirely designed by Brunelleschi.

During the same year, the construction of the dead-end tribunes of the cathedral began, with the initial plans dating back to 1438. In February/March 1446, the lantern on the dome was put into place.

Brunelleschi passed away in Florence between April 15 and April 16, 1446, leaving his adopted son Buggiano as his heir, along with a house and 3,430 florins.

Initially, the artist was buried in a tomb inside Giotto’s bell tower niche. Still, shortly after, on September 30 of the same year, his remains were solemnly transferred to the cathedral. Over the centuries, the exact location was lost until it was rediscovered in 1972 during excavations of Santa Reparata church under the cathedral.

Brunelleschi left behind an extensive and significant architectural legacy in Florence, providing a range of prototypes in various fields, from grand basilicas to central-plan chapels, from private palaces to charitable structures, and from urban planning to mechanical and military solutions.

While favoring the graphic linearity of architectural elements and profiles in “pietra serena” stone against a light plaster background, Brunelleschi also designed rich decorative complexes executed by masters like Donatello and Luca Della Robbia.

Throughout his works, there is always a dominant sense of calculated rhythm based on simple geometric principles, where each part of the building harmoniously relates to the whole.

Works by Filippo Brunelleschi include:

- Sacrifice of Isaac, 1401, gilded bronze, 45×38 cm, National Museum of Bargello, Florence.

- Crucifix, 1420-1425, wood, 175×175 cm, Santa Maria Novella Church, Florence.

- Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore, 1418-1434, Florence.

- Hospital of the Innocents, 1419-1444, Florence.

- Church and Old Sacristy of San Lorenzo, 1419-1428, Florence.

- Pazzi Chapel, around 1429-1461, cloister of the Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence.

- Church of Santo Spirito, 1436-1444, Florence.

- Rotunda of Santa Maria degli Angeli, 1434-1436, Florence.

Works by Filippo Brunelleschi

Sacrifice of Isaac

Dating: 1401.

Dimensions: 45×38 cm.

Technique: Gilded bronze relief.

Location: National Museum of Bargello, Florence.

In 1401, a competition was held by the Arte della Lana (Guild of Wool Merchants) for the second bronze door of the Florence Baptistery, and the chosen theme was the biblical passage of the Sacrifice of Isaac. The two leading contenders were Lorenzo Ghiberti and Filippo Brunelleschi. Lorenzo Ghiberti won the competition, reflecting not only the weight of late Gothic naturalistic aesthetics on patronage but also the challenges faced by a poetic approach based on dynamic values and constructive emphasis.

In Brunelleschi’s relief, the landscape plays a minor role, while the figures’ energetic character and independent actions stand out in contrast. This depiction is less plausible than the previous one (why would the servants be indifferent to the drama unfolding before their eyes?), as the artist intended to emphasize a current event’s human and emotional aspect, using a geometric structure. Brunelleschi organized the scene on two distinct planes. In the foreground, the figures of the servants are presented in complex poses, projecting forcefully beyond the outlined frame.

The servant on the left explicitly references the ancient statue of the “Spinario,” which had a bronze version exhibited in Rome outside the Lateran and is now preserved in the Capitoline Museums. Created as a genre image, the figure was imaginatively interpreted as Absalom, Moses’ brother, or as Priapus, the god of fertility, or even as Marcius, a heroic Roman shepherd who only removed a thorn from his foot after delivering an urgent message to the Senate.

Brunelleschi was not concerned with the figure’s meaning; it was merely a harmonious model to transpose into the relief under the guise of one of Abraham’s servants, a learned reference that the competition judges would have recognized and appreciated.

On a deeper plane formed by the rock, set back from the space containing the two servants, the Sacrifice of Isaac takes place, described with dramatic tones, emphasized by harsh modeling that carves space around the figures, impacted by continuous light shifts. Abraham, with determination, seizes Isaac by the throat while Isaac screams, trying to break free; the angel forcefully holds Abraham’s arm as he gazes in astonishment. Filippo Brunelleschi infuses the episode with humanity, making it contemporary: Abraham does not unthinkingly follow divine direction but intensely experiences the drama.

With this innovative and emotional interpretation of the biblical story, Brunelleschi’s use of ancient references, and his study of the corporeality of the figures, his relief can be seen as the first example of a Renaissance work, too early to gain the approval of patrons still oriented toward the International Gothic style.

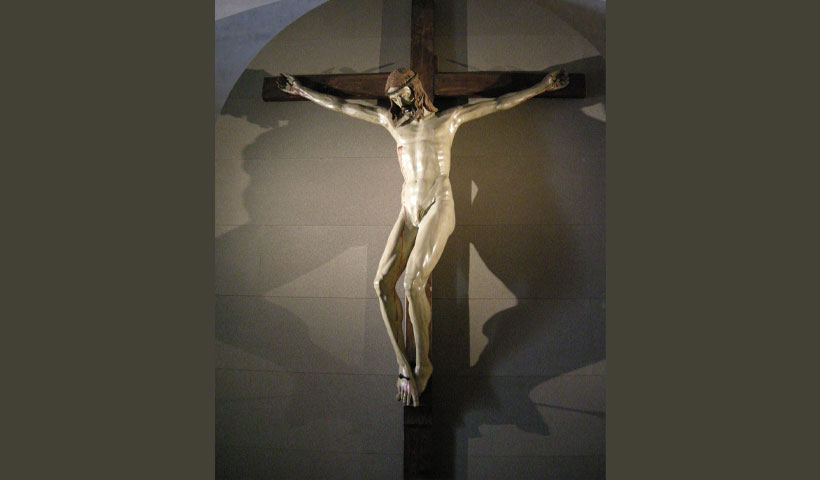

Crucifix (Crocifisso di Brunelleschi)

Dating: 1420-1425 (?).

Dimensions: 175×175 cm.

Technique: Wood sculpture.

Location: Santa Maria Novella Church, Florence.

The crucifix housed in the Gondi Chapel of the Florentine church of Santa Maria Novella is mentioned by Giorgio Vasari as a work created by Filippo Brunelleschi, who had expressed negative critiques of Donatello’s crucifix.

Brunelleschi claimed that Donatello’s work was characterized by exaggerated naturalism, making Christ look like a peasant on the cross. Vasari reported that Donatello promptly replied, challenging Brunelleschi to sculpt a better crucifix.

According to Vasari, when Brunelleschi completed the work, Donatello was so amazed that he dropped the eggs he had brought along for lunch with his friend, breaking them. Donatello exclaimed, “You can make Christ, and I will make peasants.”

We are curious to know if things happened that way, as there might have been a temporal gap of a few years between the two crucifixes. Nevertheless, the different solutions proposed by the two artists are noteworthy.

Brunelleschi approached his crucifix entirely differently, emphasizing composure and solemn gravitas and presenting a demanding theological interpretation. Furthermore, the human body is more idealized and proportionate, reflecting the mathematical perfection derived from Vitruvius’s ideal man.

Brunelleschi’s crucifix was inspired by Giotto’s work but reinterpreted Christ’s figure not in an upright station but bent on the cross with a slight twist to the left, creating multiple privileged viewpoints, generating space around the bust and inviting the observer to take a semicircular path around it.

The artwork is characterized by a careful study of anatomy and proportions, resulting in an essential (inspired by the ancient) representation that exalts sublime dignity and harmony. As in Giotto‘s cross, nothing is random or whimsical, but instead, it is the result of continuous, rational, and theological reworking, motivated by the order of the world and its elements.

Duomo of Santa Maria del Fiore

Dating: 1418-1434.

Dimensions: Diameter 51.70 meters, height from the ground 105.5 meters.

Location: Florence.

The construction site of Florence Cathedral, for which the large apse was completed in 1367 and the drum in 1410, had stalled when facing the challenge of raising the grand dome, as envisioned in Arnolfo di Cambio’s original design.

In 1307, the dome’s height, width (almost 42 meters in diameter; the Pantheon measures 42.70), and curvature (sixth) were decided upon. However, during the troubled years following the plague of 1348, the fundamental knowledge needed to construct the dome was lost.

Numerous technical, static, and construction organization problems needed to be resolved. The main issue was the cost of scaffolding, which, according to traditional methods, would have had to start from the ground up, along with the formwork to support the dome during construction.

Secondly, different machines were required to address the challenges that would arise during construction. To find the skilled architect-engineer to lead the Santa Maria del Fiore construction site, the Opera del Duomo and the Arte della Lana held a public competition in 1418. Brunelleschi, who participated with a model, won the competition, and he was joined by Ghiberti, who left the scene early.

Brunelleschi devised a brilliant construction system that, in a few years (1420-1436), allowed the grand dome of Santa Maria del Fiore, with its pointed arch, to be raised on the octagonal drum. The dome was constructed with bricks, featuring eight ribs ending in a lantern. Brunelleschi designed a self-supporting dome with a double shell. This structure didn’t require formwork (wooden frameworks), consisting of two parallel shells: the outer one aimed to protect the construction from moisture and to make the dome “more magnificent and swollen.”

Several walkways run between the two shells, allowing full access to the dome. Brunelleschi also planned the dome’s illumination. The architect used bricks laid herringbone style to manage weight and forces, in addition to the ribs and various vertical and horizontal elements. The issue of scaffolding for the workers was ingeniously resolved: at the beginning of the construction, when the dome was still vertical, scaffolding was inserted into the wall (both outside and inside); at higher levels, with the steep inclination of the masonry, a scaffold suspended in the void was created, resting on platforms fixed at lower levels, which served as material storage areas.

Filippo Brunelleschi closely oversaw the construction, personally inspecting bricks and stones, providing models to the stonemasons, devising complex machines, pulleys, and hoists, and designing boats to transport marbles and bricks along the Arno River. When the scaffolding reached the highest level of construction, Brunelleschi opened taverns within the dome with kitchens.

In 1432, Filippo Brunelleschi participated in another competition for lantern construction, which he won in 1436. The lantern is a formal and static element, uniting the ribs of the dome, resisting the strongest winds, and allowing sunlight to enter through its long vertical windows, even when the sun is high in the sky.

In 1436, the dome was completed, and on March 25 of that year, Pope Eugene IV consecrated the cathedral.

The Ospedale degli Innocenti (Spedale degli Innocenti)

Dating: 1419-1444.

Location: Florence.

Starting from 1419, Filippo Brunelleschi was engaged in the restoration works of the San Lorenzo church in Florence and created from scratch the “Sagrestia Vecchia” following a project that gained great popularity not only in Tuscany but also in Lombardy and Veneto. Brunelleschi combined two cubic rooms of different sizes: the actual sacristy, covered by an umbrella-shaped dome with twelve segments resting on four spherical triangle pinnacles, and the small altar sacristy, in which the architect repeated the forms of the main sacristy but expanded the narrow space with two lateral niches.

The walls of both the sacristy and the altar sacristy (joined in a continuous entablature) are adorned with Corinthian pilasters, arches, and profiles of windows made of “pietra serena,” which emphasize the geometric shapes that define the entire project: those of the circle and the square. Even the polychrome stucco decorations executed by Donatello (circa 1435-1443) are inscribed within these geometric forms. The overall effect of extreme purity resembles a Carolingian shrine. The exterior of the building is also simple, consisting of a masonry parallelepiped surmounted by a drum and concluded by a conical scale roof and a lantern.

Pazzi Chapel

Dating: Around 1429-1461.

Location: Cloister of the Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence.

The Pazzi Chapel was built on the site where a fire occurred in 1423 and was commissioned as a private chapel by Andrea de’ Pazzi, a member of one of the most influential Florentine families.

Filippo Brunelleschi’s design dates back to around 1429, and he also served as the project’s director from its inception in 1443 until he died in 1446. The construction phases lasted long and were interrupted in 1478 when the Pazzi family was banished following their conspiracy against the Medici family.

Precise proportional relationships define the interior spaces: the central module is a cube surmounted by an umbrella dome and flanked by two symmetrical wings with barrel vaults. The supporting elements – arches, entablatures, and pilasters – stand out with their “pietra serena” contrasting against the white plaster. A stone bench along the perimeter reminds us that the hall was used as a meeting room for the friars. The east wall opens into the altar sacristy, elevated on three steps and covered by a small dome.

The plastic decoration is subordinate to the architecture: at the top, there is a frieze of medallions with Agnus Dei alternating with paired cherubim and seraphim; below are twelve glazed terracotta roundels with the Apostles, created between 1450 and 1470 by Luca and Andrea della Robbia. In the dome’s pendentives are four polychrome terracotta roundels with the Evangelists, attributed to Brunelleschi.

Alesso Baldovinetti designed the two stained glass windows in the altar sacristy: the oculus depicts the Blessing Eternal Father, and behind the altar is depicted Saint Andrew, referring to the chapel’s patron and saint. The dome, frescoed in the mid-15th century and restored in 2009, is similar to the one in the Sagrestia Vecchia of San Lorenzo and represents the constellations present in the Florentine sky on July 4, 1442, a subject with various interpretative hypotheses.

After Brunelleschi’s death, the project was modified by adding the portico with Corinthian columns and a central arch (1461). Variously attributed to Michelozzo, Rossellino, or Giuliano da Maiano, the entrance’s center is covered by a dome decorated with glazed terracotta rosettes with the Pazzi coat of arms from the Della Robbia workshop.

Unlike most of the environments in the Santa Croce complex, the chapel has preserved its original appearance intact.

Church of Santo Spirito

Dating: 1436-1444.

Location: Florence.

A late work of Brunelleschi, the Church of Santo Spirito in Florence was mainly built after the architect’s death. Bernini describes it as the most beautiful church in the world, and it features a rich articulation of expansive and open space reminiscent of classical buildings. Forty niches unfold continuously along the walls of the side aisles and transept. The columns frame the small and harmonious bays of the side aisles, creating a continuous procession. At the crossing, where the nave and transept meet, a firmly centered space is perceived, enhanced by the converging light, which leaves the side aisles in a delicate shadow. The exterior, now closed by a straight wall, was designed initially by Brunelleschi to be rhythmically accentuated by the extrados of the niche chapels, reflecting the movement of the interior.

Round of Brunelleschi (Rotunda of Santa Maria degli Angeli)

Dating: 1434-1436.

Location: Florence.

The Rotunda of Santa Maria degli Angeli was a study in central-plan architecture for Filippo Brunelleschi, with an octagonal shape inside and sixteen facades outside. The building was commissioned by the heirs of Filippo degli Scolari, known as Pippo Spano, who, at his death in 1426, left 5000 golden florins to the Arte dei Mercatanti di Calimala to construct a Camaldolese church dedicated to the Virgin and the twelve Apostles. The Florentine condottiere had been enlisted in the army of Emperor Sigismund, who, as a reward for his victories against the Turks, granted him honors, riches, and the title of count and Spano (general) of the imperial armies.

The construction was overseen by Filippo’s brother Matteo degli Scolari, a knight and governor of Serbia, and his cousin Andrea, the bishop of Varadino (in present-day Romania, then Hungary). Both had successful careers thanks to Pippo’s fortunate Hungarian adventure. It was decided to add an external chapel to the Camaldolese monastery of Santa Maria degli Angeli, which was an important cultural center at the time, thanks to Prior Ambrogio Traversari, who became the General Prior of the order in 1436, and the presence of intellectuals such as Coluccio Salutati, Leonardo Bruni, Carlo Marsuppini, Niccolò Niccoli, Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli, Palla di Noferi Strozzi, and Cosimo the Elder de’ Medici. The project also received contributions from Matteo’s inheritance, which had passed away in the meantime, reaching approximately 5000 florins.

The execution of the project was interrupted when the Republic requisitioned the inheritance to cover the expenses of the war against Lucca (from 1437). As a result, only the seven-meter-high ruin remained, which the people called “Castellaccio.” It was embedded in the monastery’s garden wall until it was covered with a roof.

The walls were covered with a roof in the 17th century, and in the 19th century, some rooms were built on top, and the space was used as a studio by the sculptor Enrico Pazzi. It was renovated by Rodolfo Sabatini only in 1937, following the original design, but without managing to give a unified appearance to the building, which remains divided into a lower part with typical sandstone ribs and an upper part without decorations.

The designer chose to complete the Renaissance structures with a new portion, using a more sober language linked to contemporaneity – covering the hall with complete autonomy not to disturb the Brunelleschi an architecture with excessive contrasts. It has long housed the classrooms of the University Language Center, now moved to Via degli Alfani, and still belongs to the University of Florence. However, it is not currently in use.